In the early years of the 20th century, Jewish immigrant Simon Pinckovitch delivered milk for a living on the hardscrabble streets of Southside Chicago.

“On the way home from his deliveries, he would often pick up scrap metal and rags, and bring them to his backyard,” says his grandson, Marvin Pinkert. “Eventually, he and his brother-in-law, Max Patinkin, decided to go into the scrap business and founded People’s Iron and Metal.”

Years later as a teenager, Pinkert worked at People’s Iron and Metal for a summer job, as did his cousin, acclaimed actor and singer Mandy Patinkin.

“The only difference is Mandy worked in the front office because he talked a lot,” laughs Pinkert, who wound up operating the yard’s hydraulic press in the hot, unforgiving sun. “Meanwhile, my mother wanted me to go into any business but scrap metal. She worried I would wind up being the next foreman.”

In some ways, Pinkert, in his heart of hearts, never really left the scrap yard. Now the executive director of the Jewish Museum of Maryland, he serves as one of the catalysts of “Scrap Yard: Innovators of Recycling.” The original JMM exhibition will be presented from Oct. 27 to April 26, 2020, in the East Baltimore museum’s Samson, Rosetta and Sadie B. Feldman Gallery.

“Scrap Yard” explores the socio-economic opportunities presented to American Jews and other immigrant ethnic groups by the collection, storage, brokering and selling of discarded metals, rags, papers and animal hides.

In the first half of the 20th century, an estimated 80-90 percent of all scrap dealers were Jewish, according to Pinkert and Tracie Guy-Decker, the JMM’s deputy director. Today, they say that figure is between 50-60 percent.

After the museum’s original exhibition “Beyond Chicken Soup: Jews and Medicine in America,” Pinkert says JMM leaders wanted to explore a vastly different topic.

“The museum first talked about [staging a scrap exhibition] in 2008,” says Pinkert, who came to the JMM seven years ago. “I figured this topic would be a treat not just for me but for our visitors as well. It’s something different.”

Besides an array of national and local sponsors, “Scrap Yard” received two major federal grants from the Institute of Museum and Library Services and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Those grants were matched by the David Berg Foundation, the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries, and more than 20 private donors.

The exhibition was curated by Zachary Paul Levine, a former curator for the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington, and designed by Alchemy Studio of Durango, Col.

Part of what makes the subject matter intriguing, says Guy-Decker, the exhibition’s project manager, was the Jewish community’s ambivalence about the industry.

“We heard from a lot of people who felt there was a stigma about scrap – ‘Your dad is a junkman’ – even though it served an important function and was lucrative,” she says. “[Scrap dealers] are seen [by society] as polluters, but the industry thinks of themselves as the original recyclers, and they’re not wrong. Trash is a raw material, and that’s especially relevant because our whole lives are now so disposable.”

Pinkert alludes to the famous line, “The wretched refuse of your teeming shore,” penned by Emma Lazarus in her poem “The New Colossus,” which is mounted on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty.

“They didn’t want to see themselves as ‘refuse people,’ but that’s what they were,” he says of scrap merchants. “Many people converted from being small-time peddlers to scrap metal entrepreneurs.”

From Carts to Cranes

One of those people was Morris Schapiro, who came to Baltimore from Germany at the age of 16 and became one of the area’s most successful scrap dealers. Schapiro eventually scrapped the metal of the U.S.S. Pennsylvania, the ship on which he traveled in steerage to America and was pickpocketed, leaving him with only 25 cents to his name.

“He was a big fish [in the business], but there were many others,” Guy-Decker says of Schapiro, who kept a painting of the Pennsylvania in his office for many years.

Besides Baltimore, transportation and industrial hubs like New York, Pittsburgh, Chicago, St. Louis and Philadelphia were major scrap towns. A large reason for Baltimore’s role as a scrap haven was Bethlehem Steel’s dominance here.

Pinkert notes that “scrapping” was already a thriving industry in the United States by the late 19th century. Jewish immigrants were a natural fit for the field, he says, “because they were already experienced as peddlers. Also, they were excluded from other occupations, and it didn’t take much capital to start a [scrap] business. You just needed a sack and a good eye for value that was hidden in an object. … You could make a lot of money fast and establish yourself, and get your parents and siblings out of Europe.”

Scrap entrepreneurs were the originators of what we now call recycling. “The scrap dealers were major users of material,” Pinkert says. “They searched for inexpensive solutions, because they were often making pennies. They had to make old equipment last longer.”

Walking through the exhibition, visitors will feel “like you’re actually walking through a scrap yard, but you also see how the industry changed and how people changed in the process,” says Pinkert.

With the development of automation and technology from the start of the 20th century onward, the scrap industry became more industrialized and sophisticated, says Guy-Decker. The industry’s technology went from peddler carts and trucks to open-heart furnaces and electromagnetic cranes.

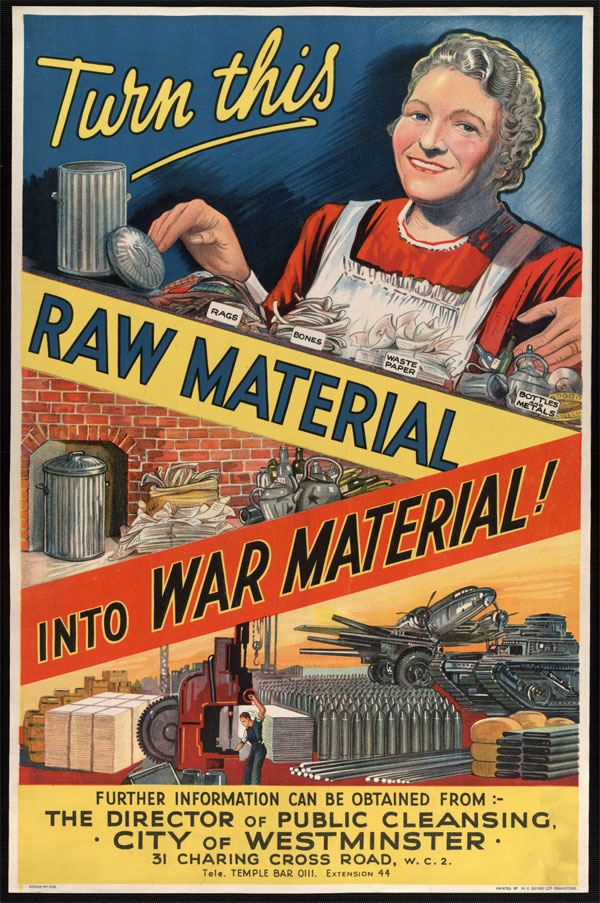

“During wartime, especially World War II, the scrap dealers and processors were more visibly essential to the general public, even more than usual,” she says. “[Scrapping] became a patriotic duty, such as saving aluminum, steel, nylon and rubber during the war.”

Grit & Glory

Divided into seven sections, the exhibition features a photo mural of a scrap yard in Western Maryland; oral histories from scrap dealers and their descendants; piles of scrap and train tracks; scrapbooks (no pun intended) of family-owned businesses, including Morris Schapiro’s Boston Iron & Metal; Schapiro’s painting of the Pennsylvania; propaganda posters from World War II; and an old employee punch clock from Monterrey Iron & Metal Recycling in San Antonio, Tex.

The exhibition’s center is dominated by a tower with drone-image footage of a Hagerstown scrap yard projected onto it. There’s also a photo mural of the H.L. Klaff Co. scrap yard in Baltimore, circa 1960, as well as an industrial scale on which visitors can weigh themselves per cubic feet of such metals as iron and gold.

In addition, a pop culture section features “Sanford and Son” bobble heads and a clip from an early episode of the popular ‘70s TV show; old wartime newsreels; scenes from scrap-related films like “The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz,” “Lies My Father Told Me” and “The Best Years of our Lives”; and the playing of such pop records as Fats Waller’s “(Get Some) Cash for Your Trash,” “Rag & Bone” by The White Stripes, and The Hollies’ “Charlie and Fred.” There is also an action figure of Watto, a Toydarian junk dealer featured in “Star Wars,” as well as footage of a 1926 ship deconstruction.

The exhibition’s final section looks at how materials on the global market are recycled today — such as clothing, bottles, grocery totes and cellphone components – and the economic impact of such industry practices.

“I’m hopeful that it will really pique the interest and curiosity of people,” Guy-Decker says of “Scrap Yard,” which will become a national traveling exhibition after its JMM run. “I hope that people will trust us that it’s worth their time. There’s a lot of history there, and I’m confident this will be a great exhibit. People won’t be disappointed.”

For information about “Scrap Yard: Innovators of Recycling,” and programming related to the exhibition, visit scrapyardexhibit.org.

(Editor’s Note: For reading materials about the scrap industry, the JMM’s Marvin Pinkert and Tracie Guy-Decker recommend “Cash for Your Trash: Scrap Recycling in America” (Rutgers University Press) by Carl A. Zimring and Adam Minter’s “Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade” (Bloomsbury Press).