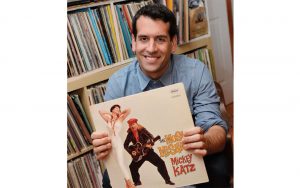

After cutting his teeth on his mom’s Nina Simone records (Dad was strictly a Sinatra guy), Josh Kohn began making a buck off of his life’s passion at age 12 by working as a bar mitzvah deejay near his home in the Philadelphia area. He used to rock a black-and-purple tie-dye bow tie and cummerbund through long hours of spinning platters by the Four Tops and Martha Reeves.

Apparently, the aging Jews of the 21st century — baby boomers, not necessarily sages — aren’t much interested in the clarinets and accordions of klezmer.

“All they ask for is Motown,” recalls Kohn. “I’d also play some Beatles and Stones during cocktail hour. Maybe the Kinks, if the kid’s dad was really cool.”

Well-mannered and affable yet subtly mischievous, Kohn often had some fun with the crowd that only another deejay would appreciate. “Sometimes,” he says, “I’d play 18-minute-long mash-ups of the ‘Macarena.’”

Well, that’ll wear out Aunt Brenda!

And while some music geeks will torture a loved one by frequently asking, “Who are we listening to?” when something special is playing on the radio, Kohn takes the inquisition a step further, quizzing his fiancée, writer Marianne Amoss, about which specific instrument is playing.

Never a musician — “I failed at every instrument I tried,” he confesses — Kohn has chased roots music, and the far-from-the-mainstream communities in which it is cultivated, all his adult life. It’s a near priestly vocation that in 2014 led to his current job as performance director for the Creative Alliance multi-purpose arts center at the Patterson Theater on Eastern Avenue.

You may have attended one of the alliance’s annual “Charm City Klezmer” events — think Mickey Katz meets James Brown in the Catskills — in holiday seasons past. Next month, on Feb. 2, Kohn will present the Panorama Jazz Band of New Orleans with Maryland native Ben Schenck on the licorice stick (aka, the clarinet).

“A lot of [promoters] like what we do, but Josh understands what we do,” says Schenck, especially noting Kohn’s appreciation of how hard it is for true believers to make a living playing marginalized traditional music.

What Panorama does — what fascinates the seven-piece band of brass squeeze box and banjo — is the stuff that simply fills Kohn’s knish: not just klezmer but the Creole beguines of Martinique, the folk music from the Balkans and Latin America, and now and again some Satchmo and Sidney Bechet.

Kohn’s office at the Patterson is less than a mile from his rowhouse on Claremont Street in a part of Highlandtown anchored by Our Lady of Pompei Catholic Church and once known as Baltimore’s second Little Italy.

Previously a programmer for the Mid Atlantic Arts Foundation in Baltimore, Kohn took the new job when Creative Alliance co-founder Megan Hamilton left for a Peace Corps assignment in Albania.

“We received more than 50 applications for the job before hiring Josh,” says Gina Caruso, the alliance’s managing director. “I needed someone who wasn’t just a cool music guy. This may be a nonprofit, but we’re also a business. He knows what it takes, knows you need to do so much more than just put a band onstage and hope that people come.”

Kohn’s specialty is curating live musical performances grounded in community — from Inuit throat singing to French/American jazz exchanges — and prompting conversations around those communities that would bring a smile to Studs Terkel’s ghost.

“I love exceptionalism and virtuosity that come from a specific place,” says Kohn.

The Creative Alliance calendar is saturated with live eclectic shows — for instance, local “astral soul goddess” Navasha Daya performs there on Jan. 21 and the Estonian fiddler Maarja Nuut appears a week later.

It takes hours of phone calls and

correspondence, perseverance, diplomacy and a knack for logistics — a key part of Kohn’s job is running across Eastern Avenue to Matthew’s Pizza to grab grub for the acts — all culminating in the privilege of standing off-stage to learn from and admire what takes place in the spotlight.

“When my work is at its best,” says Kohn, “I’m all but invisible.”

Lindy Hops, Grunge & Cracker Barrel

Joshua Stephen Kohn was born in Bucks County, Pa., in 1980, the year that New Orleans pianist Professor Longhair of “Tipitina” fame passed away. Kohn, whose family attended a Conservative synagogue, kept the bar mitzvah deejay gig throughout high school, an education in sociology, music and schtick just half-a-click away from Vaudeville.

What does such cultural immersion prepare a young man for?

Producing CDs of Americana music for the Cracker Barrel restaurant and “Old Country Store” chain of interstate highway meat-and-potato diners, of course. Not to mention becoming a shadchan, or matchmaker, between Washington, D.C., area Lindy Hop aficionados and Harlem swing dancers.

After accepting that his fate would be making music happen instead of actually making music, Kohn grew up to be one of those rare and fortunate people who can say they are doing exactly what they want to do with their lives.

After graduating from high school in 1999 — and passing through his “long-haired grunge phase” — Kohn went off to the George Washington University to pursue the ideas that undergird all of his musical interests: American Studies, graduating cum laude.

At 20, while still in college, he landed an internship with the National Council for the Traditional Arts, staying with the Silver Spring-based organization for a decade. There, he met his great mentor, longtime NCTA Executive Director Joe Wilson, who died in 2015.

Wilson was the primary producer for the Cracker Barrel music series, with cuts from Louisiana’s Balfa Brothers (who played the ’68 Summer Olympics in Mexico City) to the Sacred Steel Guitar Masters. Wilson brought Kohn in to assist.

“Joe was a true renaissance man — sharp-witted, knew when to push buttons, and fought hard to support artists and [their] communities,” says Kohn.

During one of his NCTA projects, Kohn says he experienced something that struck him as powerfully as the “hard-core country” oeuvre of Waylon Jennings (of whom Kohn laments “came too late into my life”).

“Once I did a program that included a group called the Other Europeans, made up of klezmer musicians and Eastern European Romani musicians exploring a shared, nearly forgotten repertoire,” he says. “At that same festival, we had a group of Tibetan Buddhist monks who now live in exile in India.”

Back at the hotel after the gig, all of the musicians began speaking to one another in ardent yet broken English, a conversation among insiders about what it’s like to keep cultural traditions alive while in exile.

“Hearing the Jewish musicians talk about the development of an Eastern European tradition, developed in exile from Israel, and then hardly holding on in what can be considered exile from Eastern Europe and subsequent assimilation into American culture, was a profound moment for me,” says Kohn. “It made me want to keep working with, supporting and staying prideful of the cultural expression of Jews the world over.”

But exactly what kind of Jew is he?

“I don’t like the term ‘High Holiday Jew.’ I think it implies a lack of commitment,” Kohn says, while noting “but I tend to only go to synagogue over the High Holidays.”

Perhaps it’s better to allow a fellow music-obsessed member of the tribe — string band musician Mark Rubin, from the vast and dusty shtetl of Norman, Okla. – to vouch for Kohn’s kreplach credentials.

“Like a lot of Jews, Josh respects tradition, and within our [musical heritage] he respects his elders. He sees himself as a link in a chain,” says the New Orleans-based Rubin, who released the album “Hill Country Hannukah” in 2001, blows tuba, plucks the stand-up bass and was part of the Other Europeans tour.

“Josh doesn’t make value judgments on anything that comes his way honestly, yet [he] can see a phony a hundred yards away,” says Rubin, who met Kohn during a NCTA festival in Lowell, Mass.

Rubin recalls he was once onstage, playing his heart out and shvitzing when he looked off-stage, saw a rapt listener and barked, “Get me some water!”

Kohn carried that water, and the two of them have been close ever since.

Asked how his experience of being a Jew informed his love of music — and vice versa — Kohn took his time to think through the question as one of his favorites — the late Leonard Cohen — might have. (By the way, if any musician was going to win a Nobel Prize in Literature, observes Kohn, it should have been Cohen and not that irascible, nasal little harmonica player from Hibbing, Minn.)

“As a lover of music rooted in place or tradition, the vast sonic palette built by Jews the world over has anchored me in moments where I felt I was drifting from my religious or cultural roots,” says Kohn. “In my wild imagination, there is a revival of Yiddish dance music, akin to what you might see in the old-time music scene, where young Jewish audiences in cities across the United States embrace these older sounds and make them new.”

Yes, and maybe one day the Supremes will get back together.

For information about the Creative Alliance, call 410-276-1651 or visit

creativealliance.org.

Rafael Alvarez is a Baltimore-based

freelance writer.

Photos by Evan Cohen

Zoë Reznick Gewanter, Advisor and Senior Producer, New Lens, a youth-led arts & media organization

Social Justice is far from an abstract idea at New Lens in Baltimore’s Reservoir Hill neighborhood, a youth-run media production and advocacy group formed in 2006. Zoë Reznick Gewanter, an advisor and senior producer at New Lens, knows that tangible societal change starts with young people.

Whether through after-school programming, internships or community partnerships, Gewanter says her goal is to provide a space for discussion and a platform to teach young people “how to make their vision a reality.”

New Lens focuses on a number of topics — including health, employment and education — allowing youth to wrestle with the issues they feel most strongly about.

“While having a critical voice is an important piece,” Gewanter says “we want them to share their vision of what they want to see differently in the world. Being youth-driven means that we care about supporting young people in not only finding their voice on an issue but also in working with their peers to create and put out their vision for change.”

For information about New Lens, visit newlens.info.

Noah Himmelstein, Associate Artistic Director, Everyman Theatre

While you’re enjoying a performance this season at Everyman Theatre, Noah Himmelstein is already on the lookout for the next mind-blowing production for the downtown theater with a subscriber base of 5,000 and annual ticket sales of 45,000.

To Himmelstein, a Pikesville native, the stage should not be like any film or novel but a uniquely human experience. He takes this vision to work every day as associate artistic director at Everyman, where he tries to bring “an eclectic spread” of plays and musicals to Baltimore.

In the 2016-17 season, Himmelstein will be directing “Los Otros,” a commissioned musical that he says was molded and shaped by local artists.

“It isn’t from New York, it isn’t from Los Angeles,” Himmelstein says. “This is what Baltimore has to offer.”

For information about Everyman Theatre and its current season, visit everymantheatre.org.

Sarah Edelsburg, Program Manager, Community Art Collaborative

When she first arrived on the Baltimore arts scene seven years ago, Sarah Edelsburg knew Charm City was special. Originally from New York, Edelsburg moved here as part of the Community Art Collaborative at Maryland Institute College of Art, an AmeriCorps program that places graduate students in art education and collaboration projects around Baltimore. As she worked during her year-long residency, she saw that the artists here were “tightly knit” in ways she had never seen before.

Edelsburg stayed in Baltimore and in 2015 became the CAC program director. “I still see those bonds between groups,” she says. “In other cities, nonprofit organizations are competitive for attention and funding, and that isn’t the case here.”

The program now serves 11 different organizations, helping to provide the staff needed for them to function. Edelsburg is happy to see that the application to participate has been expanded beyond MICA students to the community at large. “It’s a unique program to us, but it shouldn’t be just for us.”

~ Profiles by William Linker