The day after Yom Kippur, needing to clear my head, I loaded my bike onto my electric vehicle and took a (guilt-free) drive north to the NCR Trail. From the parking lot north of Monkton, I biked 10 miles along one of the oldest rail-trails in the country. It was a misty morning, the sun breaking occasionally through the clouds, and I was in a delightful mood.

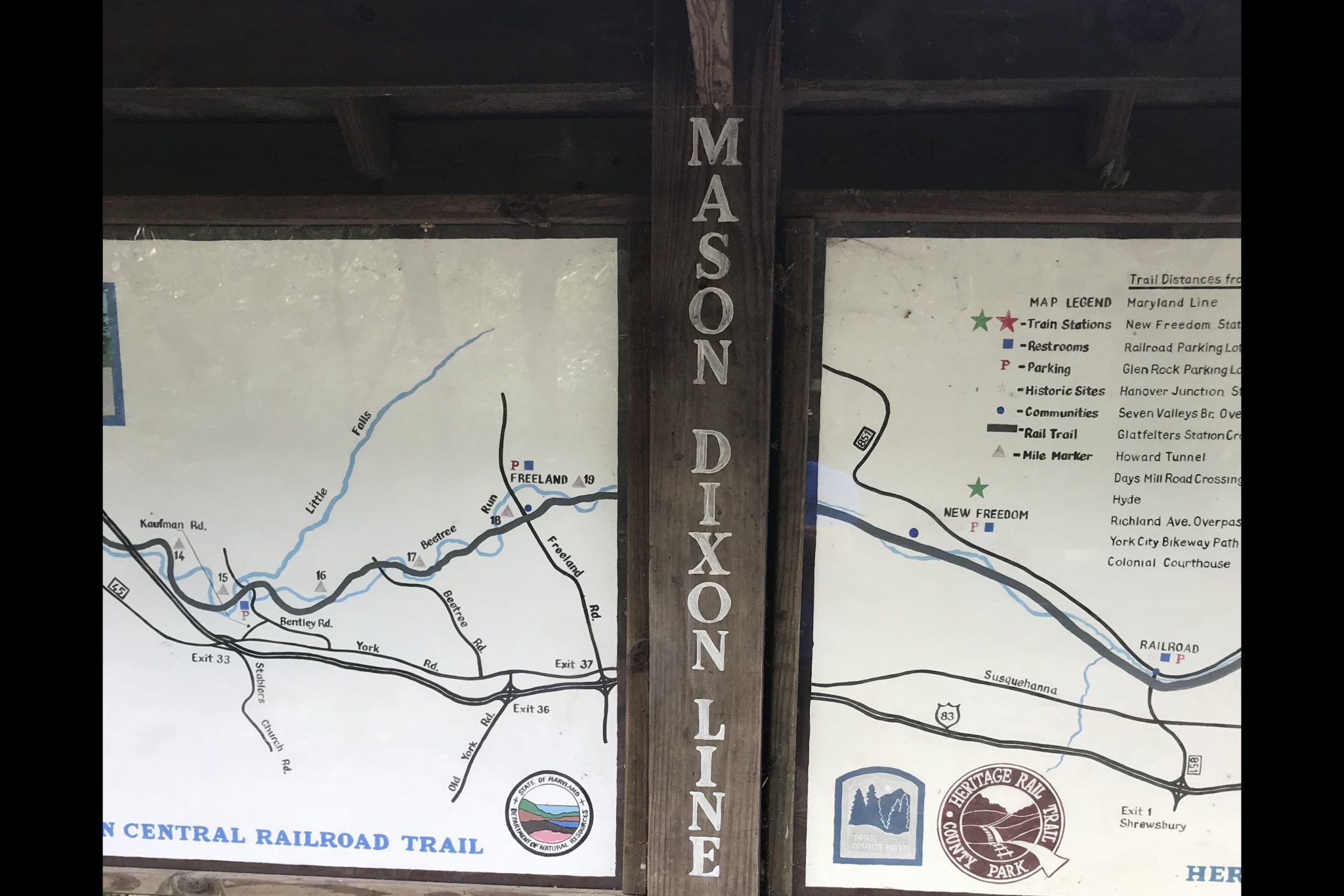

Then, I realized something had changed. The path no longer crushed gravel but asphalt, and the signage was different, too. Without knowing it, I had crossed the border into Pennsylvania. I backtracked a few dozen yards and returned to the border. A sign read “Mason-Dixon Line.”

My mood suddenly more circumspect, I contemplated the divide on which I was standing.

This is, of course, no ordinary border. The Mason-Dixon Line represented, for much too long, the division between slavery and freedom. When enslaved people escaped, they headed here. Harriet Tubman, over and over again, guided freed men and women northward to cross this line. It is a boundary separating the former slave state where I now live from the free state of Pennsylvania.

In that moment, though, something else occurred to me. The state toward which those fleeing slaves fled, the state whose landmarks include the Liberty Bell and whose territory encompasses the blood-soaked battlefield at which Lincoln delivered his Gettysburg Address, is also a state that elected Donald Trump. The state to my north, a colonial refuge for Quakers, Catholics, Jews and blacks, helped elect a man whose presidency represents, among other things, the reassertion of white hegemony.

As author and journalist Ta-Nehasi Coates writes, “Trump truly is something new — the first president whose entire political existence hinges on the fact of a black president. And so it will not suffice to say that Trump is a white man like all the others who rose to become president. He must be called by his rightful honorific — America’s first white president.”

Harvard historian Jill Lepore, in her new book, “These Truths,” quashes a common myth: that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights. Lepore asserts, rather, that it was fought for white supremacy. A century-and-a-half later, standing on the border, I was struck by how full of hypocrisy the Confederate claim had been.

While purporting to champion voices unheard at the American federal level, the new Confederacy regularly suppressed free speech, making it a capital crime to speak against the new government. While supposedly standing for individual state’s rights, the Confederacy forced recalcitrant states into their union. And with a large majority of their population disenfranchised (enslaved blacks and women), they made, through their democratic elections, a minority the arbiter of what was right and good for all.

There is a name for this sort of governance: tyranny. But the relevant question is less whether America will become tyrannical de jure a la dystopian fiction like “The Man in the High Castle” where the Axis powers win World War II or the (controversial) proposed series “Confederate” from the duo who created “Game of Thrones.”

What’s more relevant (and therefore more terrifying) is how much the Mason-Dixon Line is widely viewed as a curiosity of history instead of an ongoing cautionary tale. Hypocrisy did not begin nor did it end with the fall of the antebellum South, and as 17th century French author François de La Rochefoucauld wrote, “Hypocrisy is a tribute vice pays to virtue.”

Leon Litwack began the preface of his 1961 “North of Slavery”: “The Mason-Dixon line is a convenient, but an often misleading geographical division.” The Mason-Dixon Line once ran through the heart of America. But today, as then, it runs through the heart of Americans. Malcolm X once said: “America is Mississippi. There’s no such thing as a Mason-Dixon line — it’s America.”

Or as a therapist once told me, “You gotta name it to tame it.”

Daniel Cotzin Burg is rabbi of Beth Am Synagogue in Reservoir Hill, where he lives with his wife, Rabbi Miriam Cotzin Burg, and their children, Eliyah and Shamir. This column and others also can be found on TheUrbanRabbi.org. Each month in Jmore, Rabbi Burg explores a different facet of The New Jewish Neighborhood, a place where Jewish community is reclaimed and Jewish values reimagined in Baltimore.