In that bygone era when the Baltimore Colts were the great secular religion around here, with Sunday services conducted at an outdoor shrine on 33rd Street, 12-year-old Alan Taylor pulled off a miracle that’s inconceivable today.

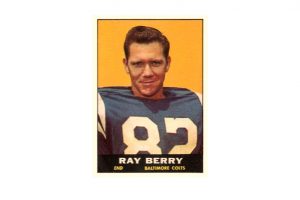

He sent a letter inviting wide receiver Raymond Berry to dinner. Two weeks later, there came a phone call to the Taylor home, off of Milford Mill Road, from a woman in the Colts’ front office asking a simple question.

“Mr. Berry,” she said, “wants to know what time he should come for dinner.”

It was 1963. Taylor sent the invitation on behalf of maybe 10 neighborhood kids, all Colts fans. But on the evening Berry came to dinner, he remembers, “We must have had 40 people in the house. All the guys, plus mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters. My mother made dinner, and some of the other women brought stuff.”

So did Berry. He brought a film projector and Colts game films. After dinner he spoke, showed movies, answered questions. He accepted a trophy given to him by the neighborhood boys who’d all chipped in to buy it.

Also, Berry kept calling home – to check on his wife, who was due to give birth at any time.

It’s a sweet memory, brought to mind now because of the intimacy once felt between fans and their hometown heroes – can anyone imagine such an innocent scenario today? – and also because of a special anniversary.

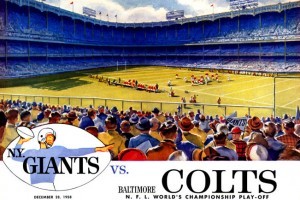

This month is precisely 60 years – Dec. 28, 1958 – since the “sudden death” game, the championship contest called “The Greatest Game Ever Played,” when the Colts beat the New York Giants, 23-17, and helped create the modern National Football League.

And whether it’s still, legitimately, “The Greatest Game Ever Played,” it’s arguably the greatest moment in Baltimore sports history – beyond World Series wins, beyond Super Bowl victories – and a story still passed down from generation to generation, like some precious family heirloom.

How do we account for its hold on so many memories?

Partly, it was the setting: the legendary American sports palace, Yankee Stadium, and an enormous national TV audience. And we were self-conscious, insecure Bawlmer, unaccustomed to being watched by the whole country.

Partly, it was the great drama: John Unitas guiding the team, mostly by completing passes to Berry, in the closing moments. That tying field goal by Steve Myhra with seven seconds left in regulation play. And then Alan “The Horse” Ameche with the overtime touchdown. Ameche wasn’t just plunging into the end zone, he was landing in the American future, signaling the great changeover in American sports culture.

And partly, it was the 30,000 fans showing up afterward to greet the team at the place we used to call Friendship Airport. In a time when we still divided our communities by race and religion, this was a great moment of emotional binding.

The game also gave us a sense of pride we’d never felt before. We weren’t smug Washington with its big politicians, and we weren’t self-important New York with its big money and glamour.

But we had Unitas and Berry, and Gino and Artie, and Lenny and The Horse. Sixty years later, and nobody needs full names to know who we’re talking about. Those guys weren’t just professional football players. They were, as Alan Taylor and his neighbors found out, working-class guys eager to be part of our community.

Ten years ago, on the 50th anniversary of the “sudden death” game, Taylor went to a restaurant gathering in Federal Hill. Some of the old Colts were there, including Berry.

“You probably don’t remember this,” Taylor said, “but you came to my house for dinner one night.”

“Sure, I remember,” Berry said. “We had crabcakes and brisket. Ballplayers didn’t make much money back then. It might have been the best dinner I had all season.”

“I can’t believe you remember,” Taylor said.

“And your mother,” Berry said, clearly delighted at the memory, “she made some great Jewish dish – called kugel.”

Touchdown, Berry.

A former Baltimore Sun columnist and WJZ-TV commentator, Michael Olesker is the author of six books, including “The Colts’ Baltimore: A City and its Love Affair in the 1950s” (Johns Hopkins University Press).

A former Baltimore Sun columnist and WJZ-TV commentator, Michael Olesker is the author of six books, including “The Colts’ Baltimore: A City and its Love Affair in the 1950s” (Johns Hopkins University Press).