Over the past few months since the George Floyd tragedy in Minneapolis, we’ve all been reminded of our nation’s troubling legacy regarding race, police brutality and social justice issues. The culture war has kicked into high gear as statues of Confederate leaders and others have come tumbling down, sparking an outcry among those who cite such actions as unlawful, misguided or mere stunts of political correctness.

To quote William Faulkner, “The past is never dead. It’s not even the past.”

Never in my lifetime has that line seemed truer.

I’ve thought a lot recently about my own upbringing and the inherent racism and myopia surrounding me as a child coming up in Northwest Baltimore. There were probably few days when I didn’t hear the pejorative Yiddish term schvartze, and African-Americans were frequently viewed in a demeaning and condescending light.

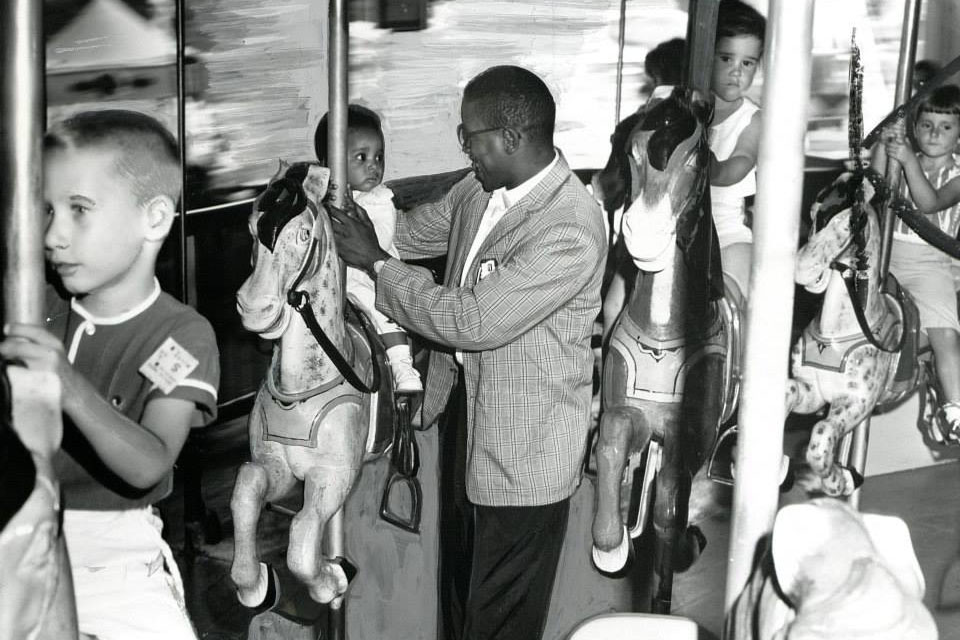

My earliest experience with overt racism came around the age of 5 while tossing a ball with a neighborhood buddy on our street, only blocks away from Gwynn Oak Amusement Park, the scene of a local landmark desegregation case (which of course I didn’t know about until years later). At one point, we stepped out of the way as a black man drove by in a truck.

“You see him?” asked my friend, before using a racial epithet I was unfamiliar with at that time to

describe the driver (you can guess which one). He then informed me, “My parents say there’s gonna be a war between us and them someday. They even have a king of their own.” (I can only assume he was alluding to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.)

Years later as a teenager, I worked as a busboy at a White Coffee Pot restaurant off of Liberty Road. It was a good first job, but I heard plenty of bigoted comments during my tenure there. One that particularly sticks in my memory was from a waitress named Shirley with a lilting Southern accent who noticed an interracial couple walk in on a busy Sunday morning. You could just see the disgust and anger in her eyes.

“Hon,” she said to me, “go over there and seat the pretty white lady and that colored man.” Being a self-righteous smart aleck kid, I couldn’t resist. “Colored man?” I asked. “What is he colored?”

She shot back a look at me that could’ve killed.

There’s no question that America needs to own up to its horrific history regarding race. The question is, where is the line drawn? After all, our Founding Fathers were largely slave owners and white supremacists, to varying degrees, and viewing history from a contemporary lens is always a slippery slope. Does D.C. need a name change? Should Monticello be turned into a strip mall with a Target and Petco?

I remember a few years ago when I worked at the installation newspaper at Fort Meade, I interviewed the wife of a soldier serving overseas. She mentioned that she was originally from Richmond, Virginia’s capital and once the heart of Dixie.

I asked her about Richmond’s famous (or infamous) Monument Avenue, featuring statues of such Confederate leaders as Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stuart. The woman, who was African-American, merely shrugged about it all.

“I’m not sure what taking down those monuments really accomplishes,” she said. “What matters is the change in attitudes out there, not the statues.”

I respectfully agree and disagree with her. We need to do both — change attitudes while removing the painful and disturbing symbols of our disgraceful past. At the same time, we can’t let tragedies and historical injustices such as genocide, slavery and systemic racism become fodder for those whose strategy is to politicize these matters and make them partisan issues that divide us.

A couple of weeks ago, someone called me to complain about my article regarding Chizuk Amuno Congregation’s recent decision to post a Black Lives Matter sign at the front of the synagogue’s campus. “There’s no need for these signs, or even the Black Lives Matter movement,” he said. “After all, we’ve already had a black president.”

Obviously, we still have an awful lot of work to do.

In this month’s issue of Jmore, we’ve asked four local writers, activists and influencers — Gail Lipsitz, Will Schwarz, Del. Dana M. Stein (D–11th) and Rain Pryor Vane — to write about this crucial juncture in our nation’s civil rights history and the Black Lives Matter movement.

We thank them for sharing their thoughts and views, and hope that you gain insights and understanding from their ruminations on this critical issue of our times.

Sincerely,

Alan Feiler, Editor-in-Chief